Solitary Encounters Seminar – Review by Sammy Playford

It feels like an age ago now, like the naive opening to a film where people make jokes about touching elbows, on the cusp of things completely changing. Held on 13th March 2020, Solitary Encounters, a seminar organised by OSR Projects, has, like everything, taken on new edges, qualities that still feel unclear within the terrifying, and ongoing nature of this moment.

Beginning the day-long program of talks, open conversations and performances, artist Mark Farid presented an overview of a selection of recent projects, with an intriguing focus on the emotional and psychological repercussions each had for him. For example, for the project, Data Shadow, 2015, (All Saints Gardens, Cambridge) Farid detailed how he gave away the login details to his online and social media accounts, inviting the audience to change the passwords to effectively lock him out of his own accounts. Farid commented, “how alone and forgotten I became”, honestly and openly calling attention to how hooked we can get to that dopamine hit of being witnessed online. Another project (Poisonous Antidote, presented at Gazelli Art House, 2016) took a counterwise approach, this time uploading data logs of all Farid’s online activity: web searches, messaging, phone conversations, which were then archived to a website. Unlike social media, where we might choose what emotional states to present to the world, what we’ve felt, thought and experienced, and what parts to keep hidden, this project purposefully didn’t discriminate, thus presenting a relatively accurate representation of Mark Farid IRL for the month of September 2018. This in turn caused Farid to confront some of his own insecurities, as connections between phone conversations and corresponding web searches could be traced, retroactively suggesting internal psychological states. Farid also spoke of how this project “validated me, played to my ego, and provided companionship even when I was alone”. This made me think about how there was this brief period when I was a child that I thought the Australian soap opera, Neighbours, was made up of actual CCTV footage of real-life Australians, and that they in turn were watching a comparable show of the UK, in which I played a small part, and how this knowledge of being watched was both terrifying and thrilling in equal measure. Though this embarrassingly smacks of my own early egotism, what it also did was bring on a panopticon-esq change to my behaviour, as I was increasingly aware of the judgement my potential Australian viewers would be watching me with. In my own convoluted way I was internalising Foucault’s prison guard, and it’s both interesting and dizzying to think of a similar subconscious impact on Farid’s own life during this project.

Leaning even further into this panopticonic quality, Farid ended his stimulating presentation by speaking about the upcoming project, Seeing I, an iteration of which is being presented later this year, in which he will wear a VR headset for 14 days, 24hrs a day, be linked with another person, exclusively experiencing what that person experiences through a video and audio relay. Setting this project in the context of a long line of philosophical enquiry into selfhood and individuality, Farid spoke of the loss of autonomy and agency that both parties will experience (himself as the viewer, and ‘the other’ – his name for the person whose life he will be a witness to), ending with the question, “without these, who really are we?”

Choreographer Katrina Brown followed with an engrossing solo dance performance focussing on minute bodily movements. Over the span of 15 minutes we watched Brown perform this jolting movement piece, as her body appeared to attempt to find itself in the space, each of her joints articulating and orienting itself in mini-loops, like a computer program running through the body’s subroutines trying to find an error. Her hands twisting back and forth, back arching out as shoulders roll forwards, hands stretching out towards the wall but not quite touching, eyes darting around the room. Brown performed something akin to a full-bodied version of a baby’s face running through the whole gamut of human emotions as it attempts to learn what it can do. This jittering performance was paired with a video projection presenting a combination of text, representational life drawings and abstract mark makings more choreographic in nature. The text, never specifically describing Brown’s movements at the moment she was performing them, rather abstracted the performing body away from the singular, as the descriptions moved away from any definite subject: “pull of shoulder blades… shrug of shoulder… bow of chin… grasp trace touch air”. This made the text less descriptive and more commanding, perhaps instructional even. As I watched Brown articulate herself, her body making minuscule movements and adjustments to itself, I couldn’t help but in turn catch my body undergoing its own hidden subroutines below conscious thought: my spine attempting to find a comfortable resting place, my shoulders pulling back, my ankles trying to ground down in relation to my big toes. Katrina spoke of how during the performance her body is “not being a social body” – and this insularity was inversely powerful to witness as a viewer (Brown even performed with her eyes closed at times, closing us off to her even further). Recalling the name of the upcoming (fingers crossed) Od Arts Festival: Alone with Everybody, Brown’s insularity inevitably implicates other bodies, be they human, sentient or otherwise in the room, drawing attention to the impossibility of ever being truly on your own.

Artist and curator Angela Charles, whose small rectangular paintings drawing on memories of landscapes and place were amassed on either side of the OSR space, gave us a confessional presentation on her coming out as, in her own words, a blind painter. Diagnosed 10 years ago with atypical Retinitis Pigmentosa, Charles kept her increasing sight impairment a secret from gallerists and collectors, fearful of that knowledge tainting their reading of her work, and becoming a selling point of its own. Charles spoke of how technology has helped her continue to paint (the app SeeingAI helps her identify different coloured paint tubes, as well as read other items out to her), and how her work changed over this period, moving from a subdued colour palette into a much brighter, bold painting style. Charles went on to talk of how she was now attempting to embrace her sight loss, speaking of her excitement as to where it would lead her work. This led to the utterly vital discussion of accessibility within the arts, noting a host of incredibly simple changes that would ease her own access to visual art. For example, gallery lighting could be much brighter (or at least turned up for an hour a day, if there were concerns about conservation), having audio descriptions near the work (Charles pointed out how even when audio guides where available, they were rarely aimed at increasing the visual accessibility of an artwork, and instead focused on supplementary contextual information). She also noted how useful it would be to have invigilators who were trained in offering audio descriptions, suggesting this be paired with personal interpretations of an artwork, to give rounded and holistic access to the visual arts.

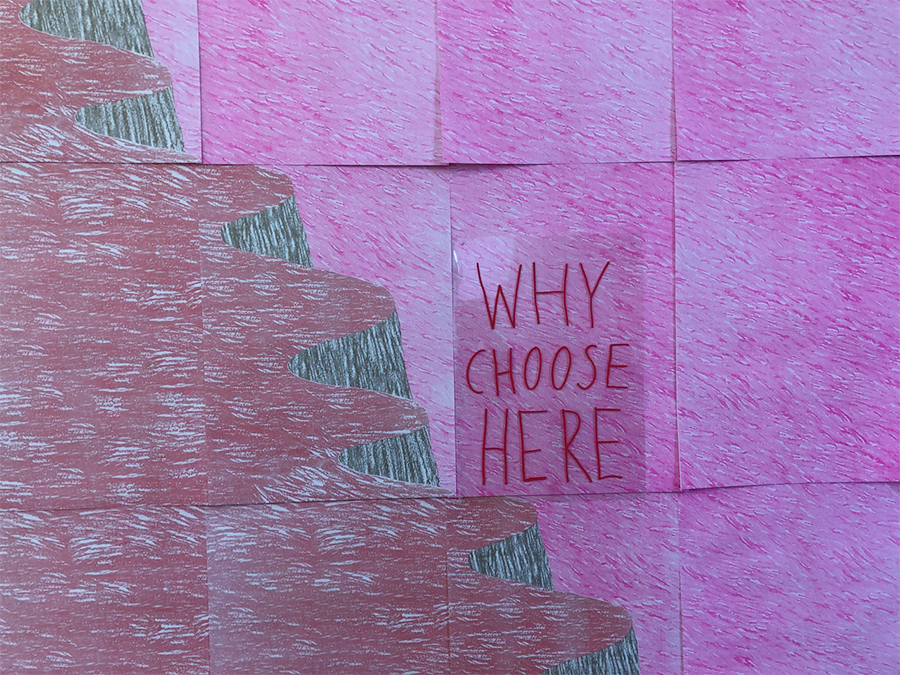

Finishing the day, Amy Gear, from the Shetland-based, artist-run project Gaada, Zoomed into the OSR space. Moving back to Shetland after completing her studies at the RCA, Gear set up Gaada with Daniel Clark as a print workshop on the Burra Isle. Essentially building Shetland’s print facilities from scratch (a twitter post of theirs notes the delayed delivery of their etching press due to stormy seas), Gear noted her desire to question the centralisation of art merely within urban centres. This was further emphasised by a project on display across OSR on the day, ERRATA (Extreme Remote Rural Artist Travel Agency): a large print of a rippling stretch of cliffs meeting a pink ocean, with questions written across the prints surface asking viewers to think about differences between the rural and the urban, who your network might be, the site of the art world for you, and what you might feel to be missing from your practice. What was striking here was that these questions didn’t feel academic to Gaada, but very deeply part of how the project functions on Shetland. As a member of a self-directed program of support for people on disability allowance, every Friday they run a printmaking workshop. Gear spoke playfully of the importance of their water urn (citing it as key to their working methods in a Creative Scotland funding application), “tricking folk into making art by making them think they’re getting tea and biscuits”. There was also a heartwarmingly utopian quality to their approach, as Gear noted the lack of any ‘art-scene’ in Shetland, and how in trying to build one, they could in turn directly ask how they wanted it to look. Circling back to accessibility, Gear drew our attention to the many people on Shetland who make art but would never call themselves artists, and the possibility that within this newly built Shetland art-scene someone with no training, making work on their own, could be on the same level as a professional artist.

She ended by speaking of an upcoming project, an activist response to the Up Helly Aa fire festival. Held in Lerwick, in Shetland, the festival is a major tourist attraction for the island in which thousands of men carry burning torches through the streets adorned in Viking attire, but that refuses to allow women to participate (on the grounds of ‘tradition’, that great immovable beast). Gear noted the regular verbal abuse that some of the main activists against the festival are subject to on Shetland, but that despite fears they might have around doing something potentially antagonistic within a relatively small community, it felt important to be “making work about things that bother us rather than are just pretty”.

It’s interesting how conversations around accessibility were threaded throughout the whole day of Solitary Encounters, but also perhaps not that surprising too. I’m reminded of Henry David Thoreau’s supposedly solitary act of ‘living deliberately’ in a cabin in the woods, and how in fact, as Oliver Burkeman points out, “Thoreau strolled back to town twice weekly, where his mother did his laundry and gave him snacks.” Isolation at whose expense? Questions of both support, and exclusion, need to be central to any discussion of the singular, solitary experience, and I was greatly reassured to see and hear that was the case at OSR.

Seminar Audio Recording (extract)

Sammy Playford is a very lazy artist who lives in Bristol. She sometimes draws guts and ladders, sometimes writes, and sometimes sings in two bands, Bunnies (with Oliver Sutherland) and Grey Faced Sibling (with Lucy Gooch). She also sometimes co-edits Doggerland (with Tom Prater), and sometimes collaborates with Lucie Akerman on The Viriconium Palace.