Driving through Somerset, on the way to the gallery, there is a worry of the car becoming stuck in what I anticipate to be a quagmire, following on from the horrendous weather. Upon reaching West Coker the warm and inviting greeting from the cheery gallery director belittles such thoughts. Nothing outlandish to distinguish the gallery from the surrounding village cottages/house aesthetic channeling familiarity that is easy to access. This Old School Room has houses OSR Projects naturally attracts a resonance with the choral, which we later find to compliment the curatorial direction of the programme.

The first solo show of their programme, this is the fourth solo showing of The Golden Space City of God by British Artist/Curator/Writer, Richard Grayson; firstly showing at the UK’s first artist-led, Matt’s Gallery, London, but the very architecture of the space, the arched roof with large wooden beams resonates the atmosphere of the community hall, beckoning the possibility that this could of very much been the first showing. Plastic stacking chairs, a very welcoming gallery dog, blacked out space and a carpet lent from Arnolfini create a first contact tension between the choral rehearsal space and cinema settings that sets up the politics of the installation.

The single channel video installation has an initial cinematography that is straightforward, with a distinction between the performers and the audience; the conductor has their back towards the camera, intent on choreographing the performance perfectly. I sit in the space, front row, absorbing the performance as though it were live.

The sung words are subtitled in a seductive fading of gold, linking straight to the title, and the Libretto abstracted from a website dedicated to The Children of God, also called The Family, a South-California 1960’s cult (as described by John Huxley) that forms the lyric of the installation. These words are to be absorbed in their fullest, as script, as text and as warning (this satirical text is not to be taken lightly as the organization unfortunately still exists and operates) in the first movement: The Arrival of the Antichrist, full of vivid dystopic imagery that takes a while to adjust, as not your conventional text for a choir.

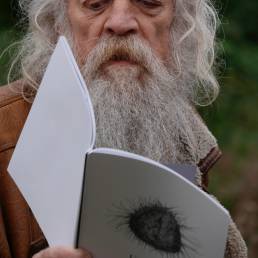

There is a disciplined stillness from the performers, bringing to mind Sonia Boyce’s For You, Only You (2007)project with Mikhail Karikis, Alamire choir & David Bickerstaff, the role of Mikhail as the active viewer, and David Skinner (conductor) as the passive, instructor, creating an interesting relationship, or perhaps even power play within the performance. Within The Golden Space City Of God, the audience adopts an aspect of the performing Karikis in For You, Only You: engaged, excited, but in sporadic bursts. By the time of the third movement; The Statue, the cinematics have become more dramatic, focusing more on the conductor, maintaining command, yet still unidentified. The third movement of the Libretto carries some fantastic imagery of ‘sub-skin PIN 666-Chip-Implants’, bubbling up Blade Runner (1982) fantasies of detection and subversion within a world in inevitable demise.

The fifth movement, The Tribulation, has an unavoidable clearness of subtle nuances in the cinematic direction that makes Grayson such a treasured artist, there is a build up, assuming to mimic a crescendo, but after the third and fourth viewing of the piece, is an effective scaling up in the performance, facilitating a slight empathy. A connection with the choir at this point has been established, their eyes darting between conductor and lyrics engrossed in the movement. “…Three and a half years…”, over and over again these three and a half lunar years serve a ritualistic purpose but leave enough ambiguousness to keep mentally searching for meaning. A constant urge to ground it, to place it within the tangible is built up, and simply left floating, a natural human desire to make sense of the senseless overrides. These cinematic and choral devices are pulled to the front, as the focusing in and out of the installation is natural over its long duration.

A glimpse of the conductors face and a few shots of the bleachers that the choir stand on shows Grayson’s deep interest in the choir as sculpture through video, exploring these viewpoints, we consider some of the performative and sculptural qualities of a choir, its collaborative aspect that seems to champion the qualities of the entire project. If we take Don DeLillo’s White Noise (1985) into consideration, “Maybe there is no death as we know it, just documents changing hands”; it provides a context for the role of authorship within Grayson’s installation if we abstract ideas in DeLillo’s novel that deal with demise and humanities natural avoidance and failure to accept death through the modern middle American family. In his previous work, Messiah (2004), we can see some of the earlier stages of this abstraction of text and use of choral activity. Again looking at collaborative practice in regards to authorship within choral contemporary video art, in Bethan Huws’ project with The Bistritsa Babi, A Work for the North Sea (1993) she discusses in conversation with James Lingwood in 2004, “It was an important part of the work that these were Bulgarians and that they were singing in England – the displacement – where none of us in the audience would understand the meaning of their words. And yet we stay to listen to them as abstract sound or pure sense with much less meaning”. This relates to the conundrum that was faced while trying to ground the total absurdity of the psudo-scripture text, we can take it as abstract sound shapes, formed in a lyrical manner or as a sensibility of the cult, Children of God.

The collaborative authorship within The Golden Space City of God is indeed a potentially constant source of research, development, rehearsal, collaboration and documents forever changing hands, rendering me thankful that Grayson not only explores his practice as an artist, but through his writings and curatorial projects. By the ninth and tenth (and final) movements, the narrative has finished condemning and ends with colourful, absurd prophecies of The Golden Space City descending and welcoming, ‘all the saved of all ages’, their ‘UFO’ a 1,500 mile cube. The choir finish and the conductor rests in the fixed position shot that they began in, bringing the piece full circle, providing a closure on the narrative, and a closing on the piece.