Weather Station (Part I & II) was initiated by Simon Lee Dicker and produced by OSR Projects during 2015 and 2016. An artist-led response to flooding and extreme weather the project explored the changing relationship we have with landscape and the natural world.

Weather Station (Part I) took place in 2015 and brought together work by OSR Projects associates Jethro Brice and Simon Lee Dicker alongside work by Alexander Stevenson (selected by Hestercombe Gallery Curator Tim Martin). The exhibition included the Weather Station structure & documentation of the journey it has taken so far alongside new and existing work by the participating artists.

Jethro Brice Born 1984, London. Grew up in Jerusalem. Lives in Bristol, UK

Jethro Brice works across media and fields of professional practice, using found materials and borrowed languages to elicit layered histories of place. He works with other people in diverse contexts, to develop collaborative approaches for an unsettled future and a contested past.

Jethro studied environmental art at the Glasgow School of Art (2006) and was recently awarded an AHRC doctoral studentship at the University of Bristol, to develop a creative geography of change in the wider Severn estuary. With Seila Fernandez Arconada he produces Some:when , a participatory public art project conceived in response to flooding on the Somerset levels, initiated with a grant from the Somerset Community Foundation. Recent exhibitions include Unruly Waters (Parlour Showrooms, Bristol) and The Power of the Sea (Royal West of England Academy).

www.jethrobrice.com

Simon Lee Dicker Born 1975 London. Lives in Somerset UK.

Simon Lee Dicker is an artist. Not so much a maker of stuff as a maker of change, he is interested in how art can connect people and ideas, changing the way we think and act. From intimate drawings and transient installations to event based social activities, each work is the start of a conversation, often exploring the paradox of being both in and of the natural world.

Oscillating between public realm projects and exhibition making he has a restless practice that is constantly on the move whilst retaining a simple playfulness, energy and intuitive thoughtfulness throughout.

Simon is a co-founder of OSR Projects and lead Artist for Weather Station.

www.simonleedicker.co.uk

Alexander Stevenson Born 1981 in Maidenhead. Lives in Bristol UK.

Alexander Stevenson mines information using processes usually associated with anthropologists, historians and researchers to create artworks, journeys and films. Huge fabric sculptures, live theatrical performances and narratives generated from remote locations are just some of the outcomes of these interests.

The work is informed by knowledge systems; how history is made and re-made through storytelling, objects and activities. He has previously explored how cultural activities, shared beliefs and personal myths can be appropriated, amalgamated, or re-presented.

Past activity includes a residency at Karst in Plymouth, a major new work for the Bristol Biennial, a commission for GoMA as part of Glasgow International Festival, a commission for Grand Union in Birmingham, headlining The Arches Live Festival in Glasgow, and a major commission for the fringe of the British Art Show 7 in Nottingham.

www.alexanderstevenson.com

Weather Station (Part I) Review By Rowan Lear

OSR Projects, Somerset

20 June – 11 July 2015

This position of exposure was best for viewing Alexander Stevenson’s video ‘Vstříc Divočině’ (Czech for “towards wilderness”). Shot in a forest clearing, the artist began a series of ritualistic and ridiculous gestures by kneading and smearing his hands with soil. He goes on to writhe in leaf litter, burrow in the earthy roots of a fallen tree and stomp on stilts bearing branches on his back. With the grimacing artist kitted in hiking gear, it’s an easy parody of the ‘outdoor lifestyle’, a leisure activity that promises proximity with nature. But the soundtrack – composed of digital growls and monstrous breathing – seemed darker, more ominous. The video was filled with odd jerky zooms, indicating an observer of this strange fauna, or perhaps turning the foolish creature’s gaze back upon the watcher.Stevenson’s other work dominated in height and colour – a domed tipi cloaked in kaleidoscope robes. Like a sea swell of festival tents, ‘Mountain’ was decked in absurd outer layers of neon – a patchwork of pink, blue, green, orange. It was tall enough to enter, and once inside, black mesh and silver stitching enveloped the viewer like a dark cocoon. Patterned with wheels, grids and lines, conjuring crop circles, desert geoglyphs and celestial bodies, the interior recalled a previous human existence, in which the seasonal and the cyclical were attended and anticipated.There was also a sense of eerie premonition in Simon Lee Dicker’s ‘Red Sky in the Morning’. From a pasted billboard, a silhouetted man gazed out to sea beneath a busy train carriage. The photo was taken before the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which would strike Sri Lanka and wipe out a packed commuter train, killing almost 2000 people. Nearby, on iPods, Dicker’s parents each retell their experience of the disaster, beginning with the moment the water struck the beachside cafe they were in. There is dark humour – it’s a breakfast-themed escapade – but also biblical dimensions, as the couple find themselves guiding blind companions towards a temple and scrambling up a mountain to escape the waters. With elements of the stories manifesting in the space (a freshly prepared Sri Lankan ‘Egg Hopper’; a chair like those they were lucky to sleep in), the work spoke of foresight and hindsight, personal myth and human endurance.But lest we breathe easy with thoughts of co-operative survival, Jethro Brice discomforted with the most exacting and critical observation in the exhibition. In a wall text, the significance of water – and a lack of it – comes to bear on Israeli/Palestinian life. Observing the black water tanks that distinguish Arab villages from Jewish settlements, the narrator realises: “…water supply is managed by Israeli companies. In times of shortage, Arab families are the first to be cut off, sometimes for months at a time.” A bird with iridescent blue wings was drawn nearby, he perched beside the words, grounded.

It was akin to a warning flash, a reminder of who lays claim to natural resources and the role that state ideology plays in necessitating, and even inviting, our resilience against disaster. As a term in increasing use – and happily claimed as a buzzword by politicians, banks and corporations, Mark Neocleous notes in Radical Philosophy that “Resilience is by definition against resistance”. Here in Somerset, and everywhere that extreme weather events occur, we need a critical eye on the response – not only that of the local community but of wider governance. What are we failing to resist? Who benefits from our resilience?

In a continuation of the project, Weather Station (Part II) will see the orb travel around the South West in summer 2016, gathering new encounters with artists. As I left the gallery, the breeze picked up, and the ‘Weather Station’ tugged, gently, at her tethers.

Weather Station (part1) reviewed by the wonderful Rowan Lear and published in contemporary art magazine This is Tomorrow

A new step towards an ecological rhetoric – Review by Martyn Windsor

Weather Station (Part 1) marks a new step towards an ecological rhetoric; one in which our tangential relationship to nature can be made visible. The works demand a distinct awareness of humanity’s reciprocal influence on climatic conditions, functioning as a wider metaphor for viewing the Earth as a whole system. In addition to these global issues, it solicits the audience’s living memories of the severe flooding that effected Somerset in 2014. As a result, the audience’s perspective is drawn from the local, to the climatic and back again in an exhibition that is disorienting, yet never incoherent.

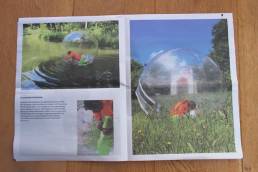

The Weather Station in question, a ‘zorb’, appears as a totem of its past exploits at the entrance to the exhibition space. Raised on a makeshift scaffold, it encompasses the actions and views of each of the artists: Alexander Stevenson, Jethro Brice and Simon Lee Dicker. The ‘zorb’ is irrepressible in its size and status as an artificial contrivance, emphasizing the intramundane realities of being separated from the environment. It is at once a perfect vantage point, but one that is totally insulated and confining – typifying our current hypocritical relationship with the natural world. If Weather Station contains a metaphor for nature and society’s ills, then the experiential confinement within its body provides the treatment. Functioning as a plastic globe, it provides a microcosmic terrarium for climate models, the participants feel first-hand the effects of their existential processes – breathing makes the restricted atmosphere warm; claustrophobic. Consuming more and more oxygen, the realities of climate change are brought into uncomfortably close quarters.

Dicker first took the Zorb out in the early hours of the morning to draw the horizon at sunrise. Marking sites that had previously felt the impact of flooding in Somerset. The documentation, reminiscent of the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic image the Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer, sets the tone for the latter contributions. Stevenson took the zorb to Hestercombe Gardens using the marks left by Dicker as navigation tools to traverse the landscape. The separation of man and nature is made ever clearer by the tracing of simple shapes of flora; Nature on the outside, a hollow line drawing on the inside. Brice rejects the ‘zorb’ as a heightened experience of being separated or removed from nature, re-acting only to its form. It becomes sculptural and exaggerated as Brice tracks the effects of the environment while taking it for a boat trip.

Inside the gallery, our eyes are drawn down the rectangular space, focusing on Simon Lee Dicker’s billboard poster, an appropriated archive image which in its scale and placement draws you in. The billboard provides the visual component of Red Sky in the Morning – an oral account by Dicker’s parents of their experience in the tsunami which struck Sri Lanka in 2004, killing near two thousand people traveling by train. The billboard’s wheat-paste has dried leaving wave-like bubbles and folds, it is an eerie backdrop to the tale, as if saturated by the very force of the ocean which shook so many lives. To the left: a stale Sri Lankan Egg Hopper, a chair, and two iPods rest on make-shift stands. The iPods contain accounts from Dicker’s parents each calmly retelling their stories from the moment the wave struck. While listening, the artifacts become contextual and symbolic of narratives both personal and profound. The billboard image of the busy train carriage and a single silhouette looking out to sea, give a sense of the Burkeian sublime with a banal reality. This is a human narrative rapped up in the vivacity of the natural world.

Drifting to the centre of the space, we are met by a rowing boat. Jethro Brice and Seila Fernandez Aconada’s traditional ‘flatner’, a flat-bottomed boat which looks at the creative responses from communities in reaction to the disastrous flooding which hit the Somerset Moors and Levels in 2013/14. Entitled Some:when 2014/2015 it proposes practical survival through an object rife with social history as we get ready for a wet future. The boat is stationary, oars cast out ready and waiting, it is more than a metaphorical ark of humanity, it is a likely a lifeline to us all.

Brice’s second work Prototype for a counter-geographical memento 2015 is a timely observation of water distribution across the Israeli-Palestinian border, looking at the impact of water as a political tool towards Arabic households, as they are the first to be cut-off in times of unrest. Styled like blueprints for a new souvenir product, Brice takes on a consumerist-driven medium as a means of furthering his critique of capitalist structures. It has a strong message to the responsibilities of man’s claim to natural resources and there use for futile and trivial forms, water here is a social force distilled with the ideologies of whomever controls it.

On the opposite wall, Alexander Stevenson’s video piece Vstříc Divočině (translated from Czech as “towards wilderness”) is set in a clearing of a forest, Stevenson begins a series of literal gestures, smearing his hands with soil, carrying branches on his back – the camera controlling our gaze shifts from tele-photo shots to close scenes of Stevenson parading around the forest. It borders the ridiculous as he attempts to become ‘one with nature’, but these actions are designed to fail; there is a pseudo-poetic gesture here about how disconnected we are. An intrinsic connection of man and nature is forged as Stevenson forces soil onto his skin, or more accurately humus – the layer of earth in which organic matter is recycled and which holds more organisms in a single tea spoon than there are people on the planet. Stevenson’s intervention with ‘nature’ here is an allegory for our lost understanding of the natural world as we all depend on the first few centimeters of soil for our existence, but pay it little attention. Our continued survival is underpinned by nature at a fundamental level.

Stevenson’s second work and the last we arrive at is a Noel Fielding aesthetic tipi, penetrating into the ceiling space. Large enough to enter, it is a patchwork of neon colours, bold and daring yet it only fully discloses itself once you enter the contrasting internal space. Calm, dark and celestial – the totem conceals an array of marks and symbols, tuned to a subconscious understanding that they have always been. Entering the tent-like object, one becomes enveloped in a night sky and the primordial visual language which oscillates between familiarity and obscurity.

Weather Station (Part 1) marks an apotheosis, a shift towards an ‘overview effect’ in one’s understanding. Commonly associated with the first image of Earth from outer space, it instigates the understanding of our planet in a bigger context – a blue dot on a black slate. The proliferation of projects which embrace this ascendant cosmology as a necessary step towards a post-Galilean view, suggest there is a consensus being reached towards an ecological necessity to consider more than our immediate surroundings. Weather Station does not force this agenda: one does not need to have their head in the clouds to understand or enjoy it; put simply, Weather Station is an explicit statement of our place. However we might perceive it.

Martyn is an artist, writer and curator who is currently working as communications manager at Spacex, Exeter’s contemporary visual arts organisation, an Arts Editor for The Clearing Magazine which publishes writing and artwork concerned with landscape and place, and an Exhibition Co-ordinator for the Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World (CCANW) an internationally recognised body for intersections in nature and culture in the UK. Thanks for for finding the time to visit us Martyn!