“Its like you have almost submerged into a world of mystical islands and sea”

Oliver (Year 2) from East Coker Community Primary school talking about Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s

Primal Tourism installation at Coker Court during Od Arts Fest 2021

Od Arts Festival 2021 – Alone with Everybody took place 28-30 May 2021, bringing exhibitions, performances, film and workshops by local and international artists to not-so-sleepy Somerset. New and specially-sited artworks popped up in cafes, halls, houses, chapels and fields around the villages of East Coker and West Coker. The digital programme continued until 6 June with workshops, performances and screenings reaching local, national and international audiences, with participants joining from as close as adjacent bedrooms in East Coker to far away as the other side of the world (Aukland, New Zealand)

With the guiding theme of ‘Alone with Everybody’, the festival explored loneliness – what it is, how we experience it, where it comes from, and how it might be addressed. The programme included playful, experimental and performative artworks that probed different aspects of aloneness, and asked visitors to consider how it might be liberating as well as difficult to be alone.

A selection of photographs by:

Brendan Buesnel

George Wright

Amelia Carvell

Katy Docking

Header Photograph – Ameila Carvell

Anna Chrystal Stephens

Adam Turner

Ben Sanderson

Bram Thomas Arnold

Duncan Poulton

Dylan Fox

Eden Mitsenmacher

Fairland Collective

Heidi Kilpelainen

Isis Whiteaway

Jakob Kudsk Steensen

Katrina Brown

Laurence Dube-Rushby

Marcy Saude

Natasha Cantwell

Lockdown Pottery

Phil Owen

Rossella Nisio

Ruth Waters

Sadie Hennessy

Tania Kovats

The Walking Reading Group

Tim Mills

Verity Coward

Zoe Toolan

Od Arts Festival 2021: Alone With EverybodyReview by Sammy Playford

@jjmoeuvres: “manifesting a dark, circular space for one…”

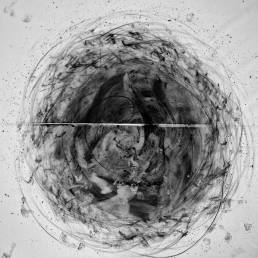

I couldn’t have put it better myself. This comment was posted alongside the opening event for Od Arts Festival on 27th May 2021 – a performance by Katrina Brown (both IRL and streamed on Instagram Live) titled 3 Em[bed]ding circle, in which the artist draws out whorls on the floor on a white square, marking her horizontal dervish with charcoal matted into her head. The black swirl casts deeper into the floor/screen space with each revolution. Presumably getting increasingly dizzy, Brown’s rounds slow, stopping as she gets to her feet – sometimes falling against the wall to steady herself – before descending back to the floor to continue her spin. It’s simplistic, but also unavoidable, to say that we viewers are separate from Brown’s internal world. What is happening for her as she connects with the ground in this way? I think about keening; a traditional Irish and Scottish mourning practice, where one or a group of women performed a ritualised wail, an intense expression of grief that accompanied a funerary procession and burial. Notably, this keening woman was usually paid; this outsourced grieving a service provided for the mourners. Is it a stretch to say that we are all mourners right now? This “dark, circular space for one” which Brown is boring into the ground with her charcoal black whirlpool, has a catharsis to it. No matter how dizzy she gets, once she’s regained her footing she descends again, for us all maybe.

I’m ahead of myself. Od Arts Festival 2021 has been a long time coming. Delayed, for obvious reasons, the festival took place in West and East Coker, Somerset, UK, and online (the parts of which I’m going to focus on here). Both the theme (Alone With Everybody), and by extension the content, despite being programmed pre-pandemic, felt eerily poignant. Across a variety of media – film, installation, performance, reading groups, workshops – the artworks and events responded to both the rural setting of the festival, and it’s over-arching themes. If I’m being honest, I haven’t engaged in anything resembling visual art (other than maybe the work of my friends) since we went into our first lockdown, so I was both nervous and ravenous to dive into the Od Arts Festival programme.

Part of the online programme, Eden Mitsenmacher’s film These Boots Are Made For Walkin’ (2017), is a vivid pastel-coloured animation of a hairy-legged femme on an absurdist journey of self-discovery. From sitting on their bed looking at their body, limbs start to dislocate before bouncing around the bedroom to a folk-punk cover of Nancy Sinatra’s titular song. It all feels very relatable; the air of boredom, being on your own, the accompanying self-scrutiny of the body that can come with that. Stretching it out, reshaping it, reimagining it. This image is playful, and the flat colours and 2D nature of the animation lean into this, but there’s also an edge of darkness, hinted at as the singer intones “you keep playin’ where you shouldn’t be playin’, and you keep thinking you’ll never get burnt. Ha!”

Marcy Saude’s Catherine (2017) was shot in black and white 16mm film during a collective filmmaking event in Cumbria. We watch a woman look in on herself asleep, the initial cinema-verite documentary set-up quickly falling away, leaving us in a fairytale hinterland just left of the real. A dreamy feeling reigns throughout, with images flowing into each other, coherence never quite coming through: walking through bracken and gorse moorland, pushing a wheelbarrow across gnarled farmland, a doorway coming off its hinges – quite literally unstable – and a round of cheese rolling down the hill. The sound design feels key to the sense of unreality. Psychedelic rock blares for a few seconds before it’s abruptly cut. As the wheelbarrow bumps across the field, the soundtrack matches what we see, but not quite; as if recorded with a contact mic, the sounds tumble over themselves with each bump of the front-mounted wheel, becoming like ceremonial drumming. We might imagine a ritual that’s happening just off screen.

Duncan Poulton’s video Content Anxiety blends a deeply pervasive, and very real, anxiety about our own self-worth (all too familiar from getting lost in social media), and an irreverently playful approach to appropriation. A digitally rendered pencil eraser rubs out an image whilst the soundtrack comprises audio clips from ‘I’m quitting YouTube’ videos. We hear these users’ sincere apologies for the poor quality of their videos, the irregularity with which they are posting, or their anxieties of viewers’ perceptions of their output, evidenced by the heartbreaking line, “I hope you guys enjoyed this video, probably didn’t, but yeah, thanks for watching.” But there’s also something hopeful about these declarations of ongoing absence; at one point we hear an unnamed YouTube user state: “[I’m] paying, like, more attention to the world and everything, not on social media a lot, so that’s why I haven’t been on, like, Youtube…” There’s something beautiful, and emancipatory in a very simple, everyday way, about that: the sentiment that ‘I’m not here making content for you because I’m off doing more interesting, enriching things for myself’.

Very much related to this is Ruth Waters’ film REDSKY66 (2016), which features the anxiety-riddled line: “I couldn’t handle the idea of adding more stuff onto the internet… stuff on top of stuff and none of it meaning anything.” The piece came out of six months’ research interviewing people with extreme phobias on Skype. It hones in on one story about a man with the fear of the concept of eternity (otherwise known as apeirophobia). It largely takes place within the familiar Skype video call, though the editing of the piece playfully toys with this. At one point the shot zooms in on the man’s ear as he worries away at it whilst speaking about his fear of never ceasing to exist, just continuing on into eternity, the image rippling outwards into nothingness. The ethics of this piece are incredibly complex, and it hurts my brain to try and talk about them. Whether any of this was scripted or performed from transcripts, I don’t know, but there’s definitely an uncanny-valley discomfort to watching it. It feels voyeuristic – the man speaking about his experience is incredibly, visibly uncomfortable. If he’s an actor he is very good at capturing the facial tics of anxiety. The piece hinges on a tweet the man sent, or was encouraged to send by a media company, that went viral. We never see the tweet, but it is made clear that it is deeply misogynistic in nature. We were previously encouraged to sympathise with this man and the complexity of his phobia, but then we get this bit of information and everything is complicated further. Victimhood, here, is a thorny issue.

With a slight shift in pace, Verity Coward’s film, Industrious Demons (2018) made me think about tape packs. Did you ever have them? Plastic packs of cassette tapes documenting raves (Hysteria and Helter Skelter being particular faves). They were big with my friends when I was a baby teenager in the mid 90s, being our only access (growing up in the rural Cotswolds, and, you know, being 11) to the utopian hedonism we perceived rave culture to be. You could hear the crowd in the background, whistles blowing, the horns; this otherworldly energy palpable. It feels appropriate somehow that this came crashing back into my consciousness watching Coward’s piece. Mediated access to being with friends – let alone your body being caught up in a crowd – is all so many of us have had for what feels like an age at this point. A large portion of Coward’s film consists of shots out of the windows of a moving car, speedily driving through damp countryside, and out of the back window we sometimes focus in on a car that appears to be following us. Is this a car chase? I remember doing this with friends, driving in convoys through country lanes. These shots are contrasted with the soundtrack – overblown dance music played too loudly through a stereo that’s resisting, distorting. Voices can be heard; banter, playful but with an edge of the sinister, like it could spill over into something more aggressive at any second. Despite conjuring up nostalgic qualities for me, none of this felt safe somehow.

On Care was the title and theme of an event by The Walking Reading Group, a project started in 2013, and run by Lydia Ashman and Ania Bas. TWRG usually run in-person events, with a planned walk around an area as the platform for conversations on a collection of chosen texts. For the Od Arts Festival it was run online. In a slightly nerve-racking twist we were paired up with another person, with whom we spoke on the phone whilst taking a walk around our local area, before coming back together again at the end for a collective conversation and debrief: separated geographically, but connected by satellites and the sharing of thoughts on our reading. This created, at least for myself and my lovely, thoughtful and lively interlocutor, an immediate intimacy; something about our voices in each others’ ears perhaps, being strangers suddenly connected on the phone, or maybe we were both just feeling vulnerable that day so didn’t have much in the way of boundaries. I do think that these last 16 months or so have made all moments of human connection, no matter how mediated, feel incredibly valuable and precious. The texts provided functioned like a springboard for us to dive into very personal territories. We touched on grief rituals, talking to the dead, queer communities, being inducted into womanhood, and, unsurprisingly, the weather. We were also provided with a beautifully designed score to aid our walking and talking, which gave thoughtful directions and prompts for bringing us back to ourselves, slowing our walk down, and making us more mindful. One of the most interesting of these to me was “listen without worrying about what you will say or do next”. Not an easy task, but one with a beautiful sentiment – allowing your own thoughts and responses to surprise you. Looking back on TWRG’s event, I’m reminded of the concept of ‘with-ness’, summarised as “an approach where we engage responsively in relationships and processes ‘from within’ our living involvement with them”. It has clearly been pilfered for use-value (as can be seen by the source of this quote), but it still strikes me as a very sweet and heartfelt concept or methodology, and one that TWRG is successfully fostering in their work.

The closing event of the festival was Bram Thomas Arnold’s Bibliotherapy For The Anthropocene, a self-described ‘faux-Quaker meeting’, that similarly (but very differently) to The Walking Reading Group acted like a twist on the reading group set-up. Over Zoom, and guided by Arnold’s preamble setting out the protocols of our time together, we sat largely in silence. Occasionally a person in the group read randomly from a collection of texts we’d all received in the post (but were explicitly asked not to open before the event) when the feeling took them, offering up reflections or requesting dictionary definitions of certain words (with disembodied hands and a large hardback dictionary fulfilling these requests on one of the Zoom windows, making it feel like an arty episode of Countdown). As the name of the event suggests, a lot of the texts were shot through with the climate crisis, with a focus on our feelings towards it – particularly hopelessness- both in a self-analysing way around the event itself (is this going to change anything?) and more broadly the effectiveness of our own actions (can we change anything?). Was this some of the grief brought up for me by the festival’s opening performance by Katrina Brown? Although these are obviously unanswerable questions, one of the nicest approaches of the event for me was the pace of it. The unplanned, free-form and improvisational approach that Arnold inducted us into allowed space to pause. Time and time again, after each dictionary definition was given back to us (in particular I recall ‘Time, Human, Awkward’, I was struck by the distance between my own understanding of these words, and the ‘official’ definition of them. Again, similarly to The Walking Reading Group, it felt like one of the main exercises we were engaged with as a group was to listen. Slow down, and listen. I’m reminded of a complex, almost koan-like line from the psychologist, educator and thinker Dr Bayo Akomolafe (referenced with urgent regulatory by Gordon White, of the Rune Soup podcast): “What if how we respond to climate crisis is part of the crisis?”

Od Arts Festival’s theme Alone With Everybody felt both open-ended and timely. Each piece wove the contrasting questions of seclusion and communality into knotty cat’s cradles which I had fun getting tangled in. Potentially because of, rather than despite, the festival’s delay, the programme felt like it had grown increasingly relevant with time. Somewhat counter-intuitively, we might wonder whether by slowing down we’re not so much left behind, as finally able to catch up.

b-side New Curators Reviews

Od Arts Festival 2021 Review by Amy Mifsud

Visiting the Od Arts Festival 2021: Alone with Everybody was an absolute pleasure to attend as my first introduction back into being able to see art in person! Heading down to the two villages of Coker, East & West I was thrilled that the sun was shining for a day of hunting round the villages to view some art.

The festival is spread between East Coker & West Coker, I picked up a map as soon as I arrived and quickly began to find my feet where I had never been before. The work did not disappoint, including a variety of art from sculptures, films, installations and even actors. I was impressed by what was on display, there is something here for everyone.

My favourite exhibit in the festival was found in Coker Court, the Court House found in East Coker. It’s titled ‘Primal Tourism’ by Jakob Kudsk Steensen. The film Steensen has created is a full-scale virtual replica of Bora Bora in French Polynesia. It’s a VR view of how this island’s landscape will look in the future from the effects of climate change. The film was shown within a large cube right in the centre of the court house, I adored the artist’s use of contrasting the historical court house and plastic cube. When you step into the plastic cinema cube, you move from the original wooden flooring to sand, sitting on a small chair to observe the film. People moving around the court house behind the translucent plastic sheeting was a brilliant curatorial choice as although you were watching a possible future of our world, the viewer was reminded that they are still in the present, there is still time for us to reflect and rebuild. Upon leaving the cube, I felt inspired by the curatorial choice of marrying the future and past in one space, placing the work in the only point in the village where people might make the big decisions that could change the future seen in Bora Bora was very powerful.

A second film particularly caught my attention during the festival. It is called ‘The Look’ by Adam Turner it is a short film in which the viewer becomes implicated in looking at an individual. The clever positioning of Turner’s film caught me off guard. Housed in the upstairs of West Coker’s Dawe’s Twineworks the audience members have to climb step stairs and walk all the down one channel in between the twine, focusing on the screen in the distance. The viewers themselves are zooming into the screen physically with the twine either side guiding them to the screen. When they finally get to the screen the music intensifies and the subject turns around to look at them. Implicating them with a glare. I found the piece very impactful, it was selected carefully for the Twineworks upstairs, curated especially for the moving image I found it great to use the length of the building of this unique structure to make a greater impact for this piece.

In previous art festivals, films / moving images have to failed captivate me, so I’m surprised to be recommending two films, but I feel their curation was what made the films so much more meaningful. Od Arts Festival have done an amazing job at weaving films into the historical environment of the villages of Coker.

An event which I definitely wasn’t going to miss did not disappoint and that was ‘G.S.O.H The Boyfriend Auditions ’ by Sadie Hennessy. Hennessey reflects on the wider cultural phenomenon that many women of the 21st century find themselves alone, despite their best efforts. The artist invited audience members to come and tell her a joke. After walking up to the Boyfriend Audition stand and hearing that ‘the best joke’ ever had just been told my nerves kicked in. I did indeed mess my joke up but that in itself was a joke, Hennessey created a welcoming and unjudgmental environment to help break down barriers and allow audience participants to have a good time, despite the bad jokes… Hennessey and her bride accomplice danced a goodbye as I left, I watched them heckle tractors passing by, encouraging the public to audition a joke!

A big part of Od Art’s Festival that interested me was the workshops on offer. Getting an opportunity to be hands on and learn from some of the artists (at the exceptionally reasonable price of £4) was brilliant. I attended the drawing workshop in Dawe’s Twineworks, West Coker with Ben Sanderson. Workshops were all in small groups so it was super easy to get hands on, ask questions and interact with other participants. Sanderson encouraged our small group to examine the flowers that had just been foraged nearby and to warm up our drawing skills with relaxed timed drawing challenges. The session evolved into creating a large ink drawing that all of the group worked to create collaboratively. It was a great way to interact with other members of the festival through creating art together. No experience was required and people of all levels of expertise were there.

Accessibility and inclusivity is an interest area of mine in festivals and something that I was impressed by at this festival. Od Arts Festivals supplied a shuttle bus which ran all day from one village to the other. Food was easily found at the festival and at each entrance to exhibits stewards were there to offer additional information, directions and to ensure everyone was safe.

I’m so glad I attended the Od Arts Festival: Alone with Everybody, I learnt from the wonderful exhibits and found their curatorial placement insightful and inspiring. This festival has done an amazing job at curating each individual work in a unique way, attendees of the festival will be surprised by the variety of work on display. I am hoping to return in 2022 to see how the Coker’s evolve.

Loneliness Dismantled at Od Art Festival 2021 – Review by Alix Emery

Od Art 2021 expanded and grew from a root of loneliness. But at Od Arts aloneness was not a howl, or a whine, but the soft bleeps of many signals meeting each other as they clicked together.

Od Art 2021’s theme was about being alone, but this review isn’t about earth shattering woe-is-me misery and loneliness. Od Art festival unravelled the experience and struggle of the last year’s anxiety, crises, increasing alienation, and debilitating racial, gender, and class inequalities. Alone With Everybody was biting into something like the post-pandemic human condition, juicy and raw. Alone With Everybody seems to have become redefined as “us”. Last year has made me genuinely happy to encounter togetherness and a friendly real-life face somewhere on this godforsaken planet, whether or not I am the one directly experiencing it. Technology had become disturbingly lively against our own inertness and there was something decidedly cyborgian infusing this art festival. The virus permeated relationships and contaminated connections not yet healed (if they ever will be). But the need for togetherness causes you to discover love and beauty in places you might not have otherwise, which is what Od Art helped made you aware of again.

In West Coker’s village hall, Ruth Waters’ Redsky66 screened cinema-style as a surreal, confessional Skype meeting: we heard a man brokenly tell his account of how one of his tweets went viral. This is something I know I dread: my past mistakes coming back to haunt me, poltergeist style. Like a slow burn horror show it unravelled for him; a woman/therapist?/artist listened. She seemed professionally outside the narrative but slipped into its feed of rumours when she finally gave in to the click bait (off screen). Redsky66 mutated between bodily symptoms, gossip paranoia and a toxic twitter culture through some sort of – equally bad – dubious digital healthcare. Empathetic connection and unknown disgust balanced precariously and occupied the molten real/unreal/virtual space of everyday oh-no-he-didn’t scandals.

Moving through farmland and fields took us closer together, alone with 90s rave hits picked up from a scratchy internet signal. This was mostly atmospheric since Zoe Toolan’s And A Vital Connection Is Made was not a fixed event but reformed and remembered from past parties by her and us – memories and voices became reconstituted in the blazing crisp rural landscape. The stillness was fractured by recollections of rough, happy shouting and by the cries of people who were laughing or sick. There was/n’t a reoccurring sound of retching and moaning, of laughter, greetings, threats and swearing, and of bottles shattering against rock. There were/n’t dirty songs in the distance. It was worse than New Year’s Eve in my mind, but 11am in a field physically. In And A Vital Connection Is Made, summer daylight’s heat haze was confused with clubs’ 3am not there, but there, drugged, close packed humidity. Rave music is saturated with affect and And A Vital Connection Is Made held up a mirror to a post lockdown subjectivity: the personal is impersonal streamed to our headphones. The hiss of a dead channel buzzed and made us all aware bodies were out of joint.

One of the most valued things I took away from And A Vital Connection Is Made was all the conversations with strangers. We talked about common connections and other things that were so alien and strange to each other. That I’d been hibernating in lockdown was made so clear in this; vegetating in my neighbourhood’s sights and smells, sleeping with not-too-bad Netflix dinners and after that spending the rest of each day doing nothing with a clear conscience. Chatting though, made me think again of ourselves together as we or us; not individually, separately, as edged and bordered with boundaries, brinks and limits, sanitised by disinfectant.

Further away, work from Sadie Hennessy set up stall subverting the tragic Miss Havisham-like alone character into one of comedy. This was as a one-woman village fete searching for boyfriends. Occupying spots in empty fields, you saw the artist dressed all in white, waiting and inviting you to tell your best jokes. There’s something almost legitimate about this style of dating. Sitting opposite each other awkwardly, Sadie Hennessy directed the humour to fill the connection: it was in the punchline and crack of laughter, it was in how you met and behaved. Dissociated machines decided your audition result, you faced two speakers; one an applause, the other a heckle from an absent stage audience: a 50/50 chance. This was a personal manifestation of aloneness, or perhaps, a dress rehearsal for finding the real right one. Sadie Hennessy reclaimed her search for a Good Sense of Humour (G.S.O.H.) to explore a biting social commentary of how many women now find themselves alone. Love has become a means of normalcy and expectation, but Sadie’s work laughs at the stupidity challenging “why?” in the gag line.

The festival expanded and grew from a root of loneliness. At Od Arts, aloneness was not a howl, or a whine, but the soft bleeps of many small signals meeting each other as they clicked together. The way we had been living as image-flesh on the screen, cyber-matter, became lives again, not presences were presences, changing our conditions of reality and altering our embodied beings. Boundary blurring, the artists were not afraid of partial identities or transforming bodies into the digital. The contemporary world is a fractured, changing multiplicity and the festival challenged the debilitating fiction of wholeness in subjectivity by slipping into and through different people and devices to make a connection. Ultimately Od Arts actually made you feel more like an alive human being who is part of something and less like a bitter ghost who is alone with everybody.

Od Arts Festival 2021 Review by Christopher Lee

It felt odd indeed. Having not attended an art exhibition or event in person for a good few years, partly down to the pandemic, and partly because of a lack of headspace, it’s fair to say I have been out of touch with how to view contemporary art. However, on 29th May 2021 I was on the way to Od Arts Festival with a fellow b-side New Curator in the car and a face mask duly on.

It was a glorious day, perfect really, for ambling around a village or two in rural Somerset. It felt good and comfortable to take time, to explore, reconnect with visual art, and to think about the how and why of the festival too. As a New Curator at b-side the trip was very much an educational exercise as well as a recreational one. I was there, with fellow New Curators, to absorb the festival as curatorial piece, to see how the thing was put together, think about why this was, and where this was.

The opening encounter was a ceramics workshop with students of the Perrott Hill School, making simple slipware dishes. It was easy, nice, and really a quite pleasant exercise in getting back to basics with making. The setting was under the roof of the Dawe’s Twineworks in West Coker, a 100m long, open sided traditional timber framed structure through which impossibly lengthy pieces of cord are stretched out from end to end. The place was a picture, tea and cake served up by gentle village folk, wildflowers sprouting up at every turn and a real essence of lovely rural England. If that all seems a bit romantic I make no apologies, I was fully invested.

Feeling genuinely regenerated after the ceramics session, I made my way, with fellow b-siders to go and seek out some art. With my ‘curator’ hat on, it did feel to me like a ‘seeking’ exercise. The supporting booklet (with maps and supporting information) seemed a complex thing to work with. Perhaps this was down to my recent inexperience with dealing with the paraphernalia of an art event, perhaps the warm weather, or maybe even an issue with its design. However, this was no great loss, the event leant itself to exploration, with signage pointing us in the right direction and a sense of discovery and adventure going hand in hand with the countryside location.

Of the artworks, a few pieces stood out. A few didn’t, but we’re not supposed to connect with it all right? I’m going to focus on what chimed with me. Adam Turner’s video piece, The Look was splendidly located on the upper level of the Twineworks. On a standard sized TV screen, you had to work to get to it, navigating the twine and traversing the old floorboards for what felt like a good mile before you realised the video itself was also playing with perspective, drawing you in to its strange voyeurism until the punchline lands. It was funny, cinematic, and slightly uncomfortable. It worked for me.

Over in East Coker, Sadie Hennessy’s G.S.O.H. (otherwise titled Boyfriend Auditions) were taking place on the village green. The viewer was tasked with coming up with their favourite joke and pronouncing it to the artist, who had a pint of cider in hand, and was donning a wedding dress. My joke was judged accordingly, and it got the unfavourable review it deserved. As a viewer I was very much part of the work, it was engaging, nerve-wracking, and a real laugh. It felt at home in the setting; like a mad historic tradition only found in the most rural of villages.

Just up from the village green and in Coker Court next to the church, a video installation piece Primal Tourism by Jakob Kudsk Steenson was going about its business waiting for the viewer to drop in. Coker Court is a grand Grade I listed manor house formerly occupied by various generations of the Helyar family. Sugar plantation owners in Jamaica, English Civil War Royalists, and MP for Somerset sit amongst the family trades (see Wikipedia). Upon entry, in a cool quiet room, we found a lightweight timber framed enclosure with transparent plastic walls housing a flat screen TV in front of two chairs. As a physical thing it was immediately recognisable as a piece of contemporary art, and sat inside, it allowed the viewer to be both physically separated from the setting, but also very much aware of its weight and history. The piece itself took us on a lush and glitchy tour of a full-scale virtual replica of Bora Bora Island in French Polynesia. The destination was abandoned, overgrown, and dense with the sounds of nature. We were exploring the place in first person as a variety of local wild inhabitants, and the video was interspersed with disparate sections of subtitled dialogue and moments of fantastical wonder. I felt a real connection between the piece and the place; exploration, the weight of history, colonialist themes, and altogether strange goings on.

The day ended on a typically peaceful note back at the Twineworks. Ben Sanderson offered up a late afternoon drawing workshop in which attendees serenely sketched plants and flora picked from the surrounding meadows as the evening drew in. If it sounds like a meditation, it’s because it felt like one.

‘Od Arts Festival: Alone with Everybody’ 28-30 May 2021.